Muscat‘s Royal Opera House welcomes Iran’s Rastak ensemble

The sharp sound of a sorna, an Iranian oboe-like instrument, pierced the silence of Muscat’s Royal Opera House. Tandem drums drove an urgent rhythm, and a chorus of voices rose in volume to fill the auditorium.

As other Gulf Arab countries fret over what they see as a growing Iranian military influence, hundreds of Omanis turned out on Thursday to welcome the 14 members of the Rastak ensemble to their capital and drink in the sounds of Iranian folk music.

“The sheer presence of Rastak is a celebration of our close ties with Iran. It’s a neighbouring country and we have thousands of years of relations,” the Royal Opera House’s Nasser Al Taee said, highlighting Oman’s determined neutrality in an increasingly troubled region.

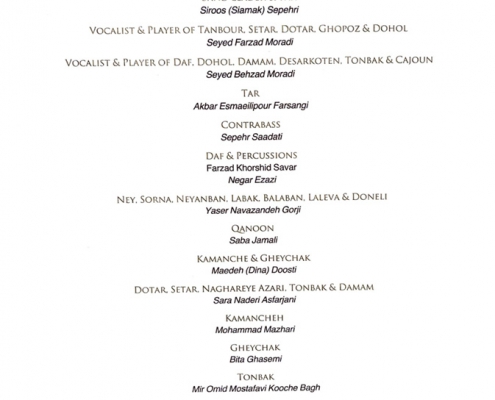

The sorna player, a young and playful man who would pick up half a dozen instruments during the evening, skipped to the front of the stage and urged the audience, a mix of Omanis, Iranians, Indians and Westerners, to clap along.

Rastak, founded in 1997 by a group of music students in Tehran, has brought its energetic brand of Iranian folk music to some of the world’s leading venues including London’s Barbican, but Thursday’s one-night performance was its first in the Gulf.

Tar player Siamak Sepehri, who leads the group, said he firmly believed music could help normalise Iran’s relations with its neighbours. But Rastak’s primary mission is to reconcile the diversity of Iran’s own musical traditions.

“We are trying to combine the regional sounds that are well known with those that are less well known… to create both a generational and geographical bridge in Iranian music,” he said.

Sepehri, born in Tehran, has roots in the southern city of Shiraz and the northern province of Mazanderan bordering the Caspian sea. Rastak’s members can trace their heritage to at least 17 of Iran’s 31 provinces, he said.

Farzad Moradi, the group’s Kurdish lead singer, said Iranian regional folk music could draw parallels with many neighbouring countries including Oman, but often at the expense of a definitive Iranian sound.

“Iran is a very large and diverse country… One of the challenges we face is that musical groups in each region typically work within their own musical tradition,” he said.

In Muscat, the fruit of Rastak’s omnivorous appetite was a uniquely varied sound: soulful laments blended into joyous dances and insistent rhythms supported lines of improvisation on a baffling array of traditional and modern instruments.

Cries of “encore” went up in Farsi and English, and Iran’s accidental ambassadors took to the stage once more.